In your book Le milieu des mondes. Pour une histoire laïque du Moyen Orient, de 395 à nos jours, you offer a secular history of the region we have come to call the Middle East. Why is it important to provide this history from a secular perspective? In the introduction, you mention that there is a “symbolic saturation” in grand narratives, what do you mean by this?

Secularism should be self-evident in any historical approach worthy of the name. But it is clear that secularism is, to say the least, being abused, even torn apart in French public debate today. This is one of the reasons why I wanted to emphasise secularity as the inspiration for my approach, all the more so since my subject of study, the Middle East, is regularly presented as being fatally bogged down by religious issues. And there is indeed a form of “symbolic saturation” of the religious dimension in the discourse of political mobilisation and justification of identity. A historian must, however, go beyond such discourses, on which an excessively literalist approach focuses, in order to shed light on in-depth evolutions, particularly over the long term.

This endeavour to deconstruct the “grand narratives” leads to the desacralisation not only of confessional interpretations, but also of ideological epics. For not all “sacred stories” in the Middle East are religious in character, far from it. There is also a “sacred history" of Arab nationalism or of eternal Persia, a “sacred history” of colonisation or decolonisation.

Die gantze Welt in ein Kleberblat, welches in der Stadt Hannover, meines lieben Vaterlandes Wapen.

Map by Bèunting, Heinrich, 1583. Map available from the Norman Leventhal Map Center

Why did you choose the year 395 as your starting point?

This date, along with the foundation of the Eastern Roman Empire, is fundamentally political, because this empire separated itself from its twin brother in the West, also Christian, in a division of the Mediterranean area that founded the Middle East as an autonomous space. Constantinople faced Ctesiphon, capital of the Sassanid Empire, which the Persians had chosen to establish in Mesopotamia rather than in Persia itself. The Sassanid and Eastern Roman Empires each claimed state monotheism, Christianity—then both “Catholic” and “Orthodox”—in Constantinople, and Zoroastrianism in Ctesiphon. Yet they coexisted for most of the next two centuries, each developing a bureaucracy of specialists in the other’s culture, in a dynamic that was more diplomatic than bellicose. This is a good illustration of the very relative importance of the supposedly inexpiable conflict between opposing religions in the Middle East.

Moreover, 395 makes it possible to avoid choosing as a starting point either the 0 of the Christian calendar or the 0 of the Islamic calendar, 622 CE, when Mohammed completed his Hegira from Mecca to Medina. Choosing one or the other of these dates, despite the best will in the world, would lead to privileging the development of one or the other of these religions at the expense of the political processes that I favour.

There are a number of common misunderstandings about the region. How do you explain them?

I admire your sense of euphemism with the term “misunderstandings”. I would rather say that the Middle East unleashes contradictory passions, all of which are based on a largely fantasised “grand narrative”. As a historian of this region I am thus confronted with sometimes virulent injunctions, especially when I dismantle this or that central myth in the propaganda of this or that camp. But, and I insist on this much more comforting dimension, I encounter a profound and serene demand for meaning everywhere, a demand, that is to say, that is citizen-based. It is to this demand that I have tried to respond with a book that uncovers issues that are out of sync with the “sacred stories” brandished by others.

I must admit that I have systematically converted patronymics and place names into French in order to make them more accessible to the reader, and in a general effort to “disorientalise” my subject. This didactic approach is served by a series of twenty maps, all original, two for each chapter, one for the whole region, the other for a more limited area and period.

I must admit that I have systematically converted patronymics and place names into French in order to make them more accessible to the reader, and in a general effort to “disorientalise” my subject. This didactic approach is served by a series of twenty maps, all original, two for each chapter, one for the whole region, the other for a more limited area and period.

Each chapter also offers an indicative chronology and a selection of references, for all those who wish to go further into the subject. And the closer my account gets to the present time, since it ends in 2020, the more I emphasise the common aspirations of the peoples of the Middle East and those of the rest of the world, starting with the European Union. This seems to me to be essential in order to overcome the “misunderstandings” that you mentioned.

With this book, you call for the necessary overcoming of chronological boundaries. Can you tell us more about this?

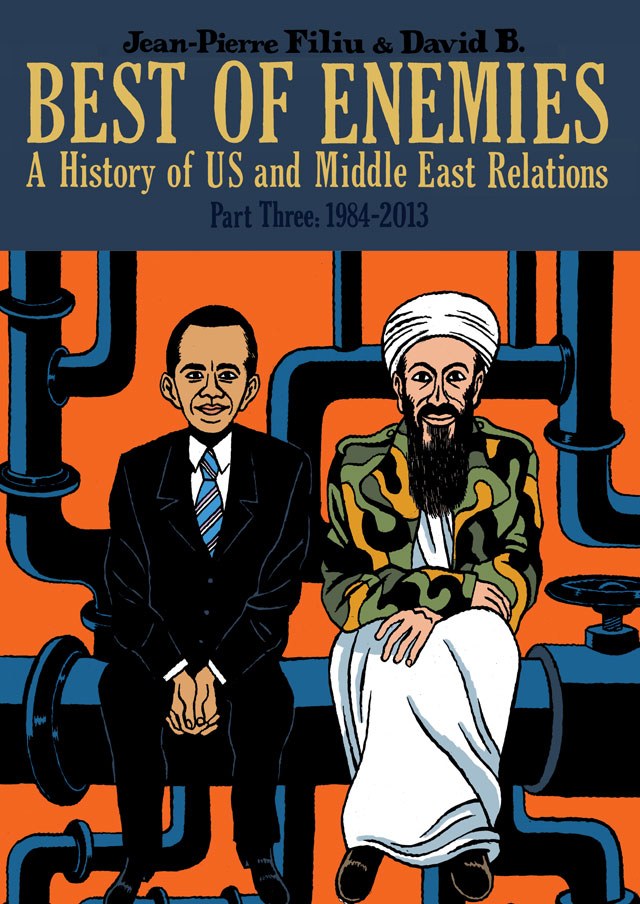

Yes, of course. I am a Professor of contemporary history myself, but I have already taken on the Middle East’s long history in previous books, such as Apocalypse in Islam, Gaza. A history, and Le Miroir de Damas. At first, I felt compelled to do so in order to highlight the lies and manipulations of modern tyrants, dictators, or jihadists, who distort the past to legitimise their own terror. However, I wanted to go further in this book in order to rediscover the inspiration that comes from studying the long term, which teaches us so much about the actual dynamics of the construction and contestation of the political.

Yes, of course. I am a Professor of contemporary history myself, but I have already taken on the Middle East’s long history in previous books, such as Apocalypse in Islam, Gaza. A history, and Le Miroir de Damas. At first, I felt compelled to do so in order to highlight the lies and manipulations of modern tyrants, dictators, or jihadists, who distort the past to legitimise their own terror. However, I wanted to go further in this book in order to rediscover the inspiration that comes from studying the long term, which teaches us so much about the actual dynamics of the construction and contestation of the political.

Henceforth, I propose a different periodisation from the one that is usually... “consecrated”. This is how I deal with the Crusades, an event that is, after all, peripheral to the Mongol invasion, in two different chapters. This is why I prefer 1501, the year of the foundation of Safavid Persia—which imposed state Shiism and forced the Ottomans who had until then been focused on Europe, to take over most of the Middle East—to 1453, the year of the Ottoman capture of Constantinople. And this is why I deal with the “long nineteenth century”, from 1798 to 1914, in two separate chapters, one dedicated to imperialist-type interventions, the other to internal developments in the region, the latter being too often obscured, at least in part, by the former.

After this secular history of the Middle East from 395 to the present day, where is your future research leading you? You have worked in a wide variety of formats, including the graphic novel, and had many different focuses, what about now?

I am lucky enough to be able to deal with the abundant news on the Middle East on my blog called “Un si proche Orient”, whose articles are published every Sunday morning on the website of the French daily Le Monde. This allows me to concentrate in my other projects on longer-term reflections.

After my latest book Le milieu des mondes, which is by far the book that required the most work, I am building up a broad range of documentation, again covering a long period of time, on the spread and use of drugs in the Middle East. My ambition is to be able to offer, when the time comes, an original history dealing with both drugs and society.

But allow me to conclude this interview by evoking the colleague and friend to whom I dedicated my book, Fariba Adelkhah, whose poignant call, made from the Iranian prison of Evin, still resounds with force: “Save the researchers, save research to save history”. Freedom for Fariba!

Select bibliography

Apocalypse in Islam, University of California Press, 2011.

Apocalypse in Islam, University of California Press, 2011.

Best of Enemies: A History of US and Middle East Relations, Self Made Hero, vol. 1 (2011), vol. 2 (2014), vol. 3 (2018).

Gaza. A History, Hurst Publishers & Oxford University Press, (2014).

From Deep State to the Islamic State. The Arab Counter Revolution and Its Jihadi Legacy, Hurst Publishers & Oxford University Press, 2015.

Le miroir de Damas. Syrie, notre Histoire, Editions de La Découverte, 2017.

Interview by Miriam Périer, CERI.

Keine Kommentare:

Kommentar veröffentlichen